The Grasp

[part 1 of Contact, Candle, Ampersand (2025)]

The last time, baby, that I came to you— Oh, how your flesh and blood became the word.

Scritti Politti

I won’t reach the final nakedness. And I still don’t want it, apparently.

Clarice Lispector

I wanted to write honestly. Not “write” — I wanted honesty. It was June and it was always another June: somehow always the one I described and not the one that I lived. The dinners ended slowly and carefully, with Solomon’s list of things he saw on the way home, then a quiet turning of our gazes toward the cherry tree, and at the moment we would run out of phrases from one another’s language there would invariably be a succession of scents from all corners of the neighborhood, each one too fast and final to ever become a thought. I wanted their honesty; I wanted to put them all in the poem. And it was the next June, and it was the summer of objects; bins of free DVDs, ceramic pots, pebbles we rolled over, yellow volumes of Kant and Hölderlin. When you’re a child the world is composed of so many instants of enormous newness, and yet you find that it must all be properly sorted and apprehended by the mind of the adults around you, the sources of the explanations that make all these objects intelligible. You take immense comfort in what is intelligible, and in the fact that you, yourself, are one of these intelligible things, that anything you see or feel or are is probably intelligible if someone gives it the right words. And you begin to give these words to yourself, as intelligibility seems the already-perfected strategy for understanding, for being understood, seems a state so sublime as to get you beyond your own body.

And now there is the feeling that something is covered-over. And now the library fills with so unexceptional a loneliness that is anyway so swirling and irreducible in its origins, so ridiculous to try to find the words for. I wanted to put it all in the poem, and still the charming gales of what moved me, and I wanted the soft touch of understanding to graze me from all directions, like so many particles of oxygen and songs from passing cars, emanating out of and into me without anyone even having to try. I wanted perfect understanding to emanate out of and into me. A savory and self-perpetuating honesty by which my life might be intelligible.

How does a life become intelligible? The air conditioner is humming. Crows there. The grain of wood is perpendicular to the screen, blank blood-upright, where writing takes place. Last night at dinner I texted Ella under the table that yes I got their postcard and will reply soon, though I don’t know what I could write to distill the four months since we last saw each other — at the Trident, when they’d had to drive into town early to avoid the thunderstorm, and Michael appeared with his hat and his Robbe-Grillet book at the table opposite, which was real coincidental timing because as it turned out he was just about to catch his flight back to Portland later that afternoon — into a set of statements, questions, a set of syntax so well-extracted, so properly derived and divined out of the surface of my days as to be honest and interesting. Would I mention the air conditioner, or the writing I would be trying to do the next morning on the third floor of the library, at a stranger’s desk near the Russian history shelves? Would it begin with the drive back to New York, screaming flies in Indiana and Love’s gas station prices sprouting like prehistoric plants, right leg aching warm ginger ale, the single cloud that made me think most clearly of the soccer field by their mom’s old house… What nights should figure into this update, what feelings from what nights, and for that matter what thoughts from what days, which salt and which dead leaves? What instants should be changed into instances, say, of facts about my self, worthy of space on the card?

N-746 VIEW OF RUMBLING BALD MOUNTAIN FROM TERRACE OF LAKE LURE INN. LAKE LURE, N. C.

The area near the Russian history shelves is very cold in the morning and in the morning in the haste of autumn I find that my navy sweater still smells a little nauseatingly like campfire smoke after five days and one wash, a smell that’s now somehow indistinguishable from the perfume Kate had on when she stayed over for the second-to-last time, probably after Mahler Four and Solomon’s trailer, when the two smells compounded on our pillows. Put it all in the poem. The writing takes in the light from the east window, no: The writing takes place in the light from inside my laptop, and the writing takes place in the cold rotoscope of this time last year, in the sickness from last week’s apartment, in the dull froth of last night’s conversation, hearing the dawn coming in from the kitchen, not too tired, not too much blue.

Does a life become intelligible? The dream to put it all in the poem and the postcard makes the promise of a witness, a witnessed life. Right foot flat against the ground. Huge red apple Henry left on the table, bitten parts turning yellow. The life of so many places and acts; the white page of overt simplicity. And so the opacity is overcome: signs make me intelligible and make me, every harsh angle redeemed by its capture in the word. What is missing?

How the page leaves me alone. How the security of the page threatens me with a solidity within a transfiguration…. Extracting, from these flowers of sense, the sense of a place in the order. Of symbolic marks and values. To be held, ever-present. The sensory becomes the sensible before it has even left that initiating partition between the cricket players at Pershing Field and my answer to what happened yesterday, which I give to you timidly at the opening and thereby become a line through some imaginary matrix and not a series of images. How the sound intervenes in the situation, all our bodies coarse with the freeze and thaw of language, that peculiar technology capable of splitting away from the world it names. And so all through the city, people parallel to themselves— in their monologues, the movement of stuff. O! To be held, ever-present.

Intelligible (adj.) from intellegere "to understand, come to know" (see intelligence). In Middle English also "to be grasped by the intellect" (rather than the senses). Intelligence (n.) late 14c., "the highest faculty of the mind, capacity for comprehending general truths;" from Proto-Indo-European root leg: "to collect, gather.”

does language collect or make ?

does language collect or make transmissible?

what does language collect or make transmissible?

O! To be grasped by the intellect. The highest faculty of the mind. And yet, the bitter loss— the longing for what drips off between the knuckles, resists that collection and capture. The excess of the actual that wants to ascend to the purity of form. Such is the purity of your love.

I try to protect the actual from the gust of this gesture: The air conditioner is humming. Scent of your last return, with mascara, soup cups. And then the thought that these are not, are never the actual… that these have already been grasped, clutched, named, made intelligible. Collapsed and affixed to the general.

Where is the language of my body?

In heaven everything is sound; the material tangles of the actual are sorted and stilled. And how! Apprehended, closed into the machinery of mouths. And how! Into a single language….

"a human being must understand speech in terms of general forms, proceeding to bring many perceptions together into a reasoned unity. That process is the recollection of the things our soul saw when it was traveling with god, when it disregarded the things we now call real and lifted up its head to what is truly real instead" (Phaedrus).

A partial history: Plato instates the divide. “What we now call real,” the real of the present, the real of our bodies, lies in the mythical shadow of “what is truly real.” Truly real are the forms which reside in the heavens, their smooth generality extending quietly over the surface of all that is particular, all that we might encounter down here. Plato instates the divide between the sensory and the conceptual in such a way that the former is a representation of the latter, a set of flimsy, impermanent replicas of the true objects of knowledge that reside up there. Our bodies can never bring us this heaven, but its presence can be invoked by the unification of scattered perceptions which is enacted by speech, this leveling of sensory experience into intelligible parts and wholes. And so “speech” and “forms” gain an affinity in the assemblage — “speech in terms of general forms” — where language intervenes as the locus of a re-collection that organizes perceptions under the reason of the truly real.

In Plato, the form of the philosophical dialogue is the apparatus of speech which can most sustainably act as this first step toward contact with the forms. The Socratic figure has an acquaintance with them, an eye to the outside of the cave, and by a dialectic accumulation of statements and questions his interlocutor may arrive at an orientation in the same direction… the direction of Truth. And so the image spreads outward until we cannot trust our bodies but can trust words — especially the words of the philosopher — to put us into contact with what is finally real.

"Only a few remain whose memory is good enough; and they are startled when they see an image of what they saw up there. Then they are beside themselves, and their experience is beyond their comprehension because they cannot fully grasp what it is that they are seeing."

The images are particular, superficial, whereas the things to which the images point are universal— and it is to this universal plane that speech can properly orient us.

What is it outside the ambit of our images, our comprehensions and graspings?

What is the experience beyond?

Comprehend (v.) mid-14c., "to understand, take into the mind, grasp by understanding," late 14c., "to take in, include;" from Latin comprehendere "to take together, to unite; include; seize." from com "with, together," + prehendere "to catch hold of, seize."

No crows on the lawn now. Lunch and sunset, alpine for the outline. Last night at the movies: frightening muddle behind my eyes when I remember the drive back from the mall. Today: more rain— Twitch in my index finger from the train to Pennsylvania next week, vague stomach pain from the screenshot Anna sent me on Thursday from her Czech number. Put it all in the poem. Seize something and take it in: each feeling a thing, each thing a thought, each thought a word. Each word drawn from a history of words, of other people’s thoughts and feelings. How does a life become intelligible? Is it only through this violence to the actual?

"...each word immediately becomes a concept, not by virtue of the fact that it is intended to serve as a memory (say) of the unique, utterly individualized, primary experience to which it owes its existence, but because at the same time it must fit countless other, more or less similar cases, i.e. cases which, strictly speaking, are never equivalent, and thus nothing other than non-equivalent cases..."

"Every concept comes into being by making equivalent that which is non-equivalent. Just as it is certain that no leaf is ever exactly the same as any other leaf, it is equally certain that the concept 'leaf' is formed by dropping these individual differences arbitrarily..."

Friedrich Nietzsche, I do admire your lateral paddles. “On Truth and Lying in a Non-Moral Sense” is a sensational essay. And how your anger at language lays the ground for your clamoring Copernican task: to rid yourself of abstract heavens, to refuse to seize-together….

Nietzsche imagines a language that can bring its reader or listener “a memory […] of the unique, utterly individualized, primary experience to which it owes its existence,” and bemoans the fact that what language instead gives him is a concept, an object that becomes available to the grasp of his intellect only through its estrangement from that experience. The concept, that generalized element of the intellect-space which is what’s really designated by the word, is equally applicable to any number of particular instances we can experience in the sensory-space… and so the particularity of those instances is erased at the moment of their being named, removed from our immediate senses so as to be intelligible to others.

What is sacrificed here, F.N.? The primary experience to which the word owes its existence…. The word is in debt to the experience, of which you figure the word as a pale, secondary offspring. A word might do its job if it gives you a memory of that experience, returns you to the orbit of that experience’s rapturous primacy, hands you back over to the world of your senses. But because it is weighed down by an excess of other possible experiences, in fact “countless […] non-equivalent cases”… the word is never enough. Do you want your words to be loyal to you and your experiences only? Would this not bar all communication? It is obvious that you cannot put your exact experience into another person’s body, or even into your own body for a second time; the plainness of this fact should tell us that doing so is not a role language plays in our lives. Yet the possibility of your experience becoming transparently transmissible is so enticing…. Does it make you fear the word having to leave your mouth and melt onto a different tongue?

"The desire that is stirred by language is located most interestingly within language itself—as a desire to say, a desire to create the subject by saying, and as a pervasive doubt very like jealousy that springs from the impossibility of satisfying these yearnings" (Lyn Hejinian, "The Rejection of Closure").

Very like jealousy. Jealousy that the word makes contact everywhere. What about this leaf, F.N., this utterly individual leaf, demands that you retain it? Restrain it? Is it not amazing if the word makes contact everywhere! And is your desire, which so often is my desire too, not simply a frantic desire for a graspier kind of grasping, a way to make the actual persist… in a new and better language, one that will not betray our bodies… one that will allow us to exchange with one another not our concepts but our feelings, fully intact, the way we experience them ourselves….

Lamp-clouds in powerlines; blinds and stone. A little pit from the day getting dark, so early, so sweet and furious smells. Two women having a long conversation in Chinese next to the kids in Adidas track pants who glance around when they swipe the nicotine out of the air. This time, maybe, we’ll catch it.

How do we account for the primordial separation which still organizes this schematic— the one that separates experience and language as two fundamentally opposing poles that constantly attempt to reach one another? Nietzsche’s image is an inversion of Plato’s, certainly in what is valued and what is devalued, and yet the terms and positions seem ultimately the same. Language discards the singularity of the experiences it names and brings those experiences into a reductive realm of the general-conceptual: for Plato this is a triumph, for Nietzsche an emergency. The “twisting movements” which are arbitrarily designated in the conceptual field as either “snake” or “worm” gain their own kind of deific presence in Nietzsche’s grief— still there is an insurmountable gulf between the general and the particular, and still one of those elements can never allow us to reach the shining beacon of the other.

I am not particularly moved by leaves or worms. What is at stake for me in language is closer to what happens when the sazerac glow wakes me up in the middle of the night, and the rain for tomorrow has started to come down in muddy crinkling sounds, and inevitably I begin running through all the different ways I might have responded to the comment Jeremy made and the hand he put on my knee just after I got off the phone and just before I crept into the guest room. The feeling from his gesture is still hanging meanly in my stomach, and I think of bringing it up tomorrow, but there seem to be an infinite number of ways I could try to cram it into a framework of expressible ideas that make it rational and empathetic. The feeling is too big and too tender for any of these, and involves too many factors stirred from too many years ago; the naming, the linear timeline, the implicit cause-and-effect which language seems to demand, could never be sensitive enough to convey the feeling. all its simultaneities. Still, I take part in that horrible Cartesian insomnia, during which one thinks they can solve their life simply by formulating it into the correct thoughts, and soon all of the equally plausible and equally insufficient ways I could word the feelings to Jeremy melt into a stream of imaginary, one-sided speech that has nothing to do with my interpersonal reality. And at coffee I don't mention it, or later.

And the recording I tried to take of the crinkly rain sounds is totally silent.

Fiona tells me that she thinks almost always in streams of sentences, that speaking is for the most part only a putting-forth. I have never witnessed this parallel— I have the silence of the room and I have the feeling that something happens. In high school I would get migraines that included few-hour bouts of what’s called Broca’s Aphasia, during which I could understand speech perfectly well but couldn’t produce the sounds to make it cohere. So I would have a thought in my mind but my mouth would slide and settle around all kinds of words whose sound-shapes were similar to my thought but whose sense was entirely different. What a startling tragedy, then, in how similar sounds could not bring forth similar feelings, how this simple fact seemed to reveal the entire apparatus as a sham….

"Psychologically our thought—apart from its expression in words—is only a shapeless and indistinct mass. Philosophers and linguists have always agreed in recognizing that without the help of signs we would be unable to make a clear-cut, consistent distinction between two ideas. Without language, thought is a vague, uncharted nebula. There are no pre-existing ideas, and nothing is distinct before the appearance of language" (Course in General Linguistics).

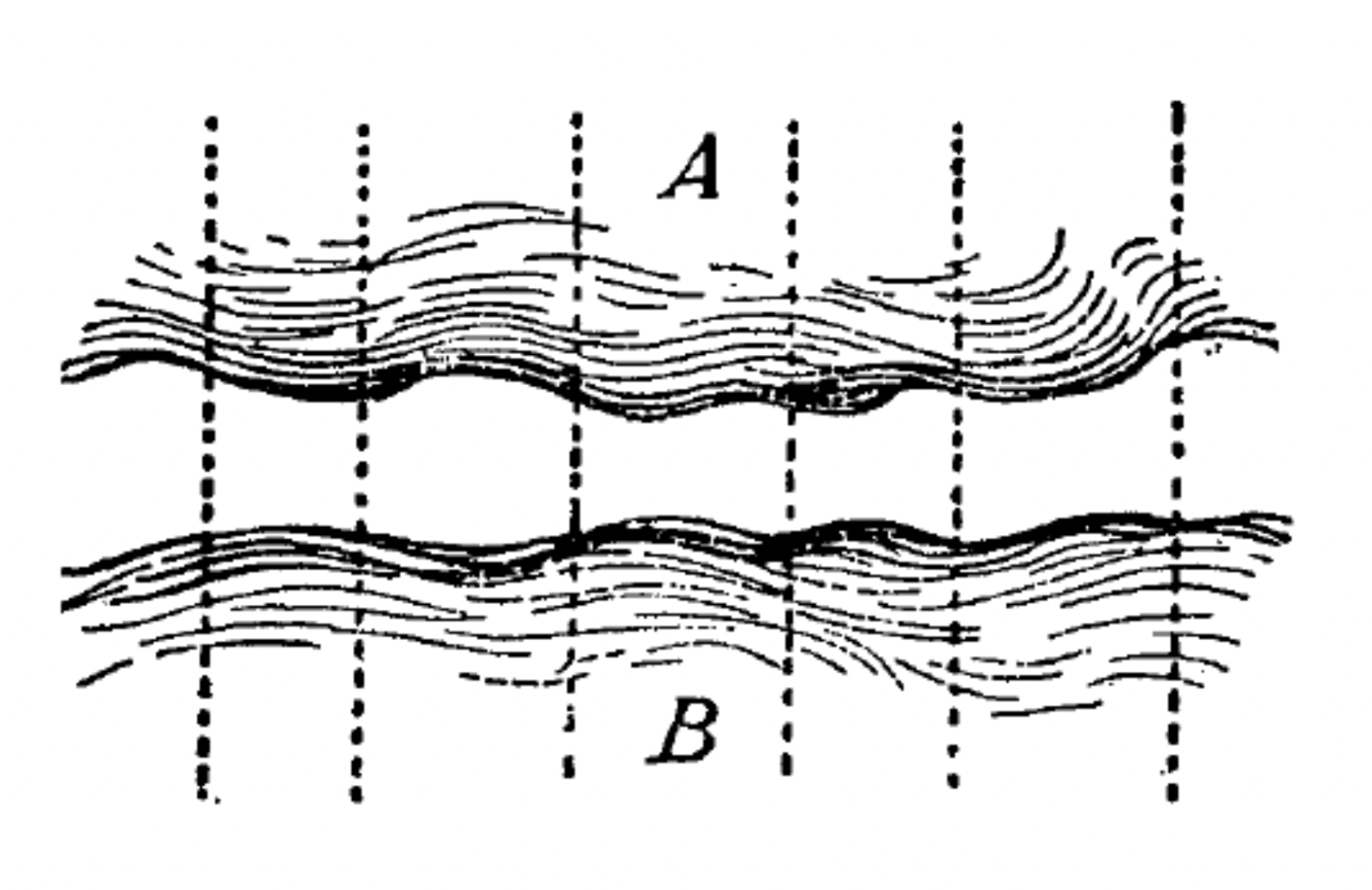

Where does the appearance of language take place? This appearance is a key but unstable moment of the structuralist picture inaugurated by Ferdinand de Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics. Against what background does language make its entrance? The thought and the sound must be two separate planes for there to be a “before the appearance,” and yet they are famously as inseparable as the two sides of a sheet of paper — “thought is the front and sound is the back” — implying a primacy of the signifier that would become essential to his successors in structuralism. Why then the alienation between the two planes, the gulf between the sound and what it corresponds to?

And what does the sound correspond to; what, if anything, is there to be made intelligible by signifiers? (What is in my head or stomach before the words match or falter? Before the words head or stomach….) Saussure, in answering, resorts to strange phrases: a “shapeless and indistinct mass,” a “vague, uncharted nebula.” Because surely there must be something for him to locate as “before” language, lest the “arbitrariness of the sign” risk incoherence (if there are already signs in our heads, we need not separate them out as “signifieds” arbitrarily linked to “signifiers”). So these terms (mass, nebula) sit in the precarious position of at once maintaining the “signified” and “signifier” in a coherent opposition — asserting that the “psychological” and the “linguistic” can never be on a horizontal continuum with one another — and asserting the reliance of the psychological on the linguistic in order to become… what? Become an actual thought? Become shaped, distinct, ‘charted’?

Émile Benveniste, in the lineage of Saussure, tries to clarify the inseparability of thought from language, but we see that his pictures when writing about both (still, go figure, separately) are just as strange:

"Linguistic form is not only the condition for transmissibility, but first of all the condition for the realization of thought. We do not grasp thought unless it has already been adapted to the framework of language."

"As a matter of fact, whoever tries to grasp the proper framework of thought encounters only the categories of language" (Problems in General Linguistics).

For as much time as Benveniste devotes to arguing that whatever we normally call “thought” cannot actually be imagined as “prior” to its formation in and by language, the actionn of grasping remains a quiet figure separating the one from the other. After all, the distorted mirror between the first two sentences above — Linguistic form is [...] the condition for the realization of thought. We do not grasp thought [until...] the framework of language. — seems to set up an algebraic equivalence between the “grasp” and the “realization”: thought can become realized, can enter into the space of reality, at the moment we can apprehend it. Must something be graspable in order to be real? I suppose, in many cases, something must be graspable in order to have a theory written about it, as grasping seems a pertinent verb for how we normally imagine “understanding”— the capturing of something perceptual or sensory by something that makes it intelligible, describable.

But certainly, I plead, there are things that feel real “before signification,” things I want to characterize as “thoughts” that do not easily magnetize to language. For who of us hasn’t sustained an intimacy with the ineffable— with twisty liquifying thoughts that resist being grasped, made solid in the legitimacy of signs? Do we not, really, feel the constructedness, the arbitrariness of our words sting through our every tissue in each tangling emotional conversation? The ridiculous task of wadding together all the stuff sloshing in our hearts our heads innards and all the tightnesses in our throat all our joy and jealousy all my elbow on the center console sad dreams two nights ago or last year all the width of my childhood home my dad’s jacket all the taking my finger off the radio dial and trying to find Cassiopeia above the soccer field, wadding together all this stuff and handing it to you, complete and delineated, as a series of words that reflect my inside outward, you and I being perfectly real? This stuff feels like undelineated thought, like a ‘vague nebula’ unassimilable to and assimilated by language.

Might we say that this is not thought but only feeling?— but then, where does the distinction between feeling and thought take place? Must it be in the realm of thought? And must the distinction between thought and language take place only in the realm of language? Who tells me which things inside me are thoughts, and which are feelings, and which are already words?

Certainly, in considering the plane of experience that comprises something I call “myself” or “my life,” there are things which feel opaque to language and things which feel constituted by language. In this latter group, maybe, the group of things unimaginable without the categories and delineations by which language makes my perceptions manageable, I place the objects of Nietzsche’s concern: it is only as a fantasy, after all, that I ever find the experience of a “leaf” that has not already been clarified into the familiar conceptual category “leaf” (a category which, by itself, never accounts for this leaf’s particularities).

But every day I also run up against the experiences which do not seem to fit into the structure of words and sentences easily if at all. These experiences most often belong to what we might usually call the “interior” space: emotions, memories, the disarrayed and unwieldy thoughts taking place as I type this. But the interior-space is, of course, also forever present in the experience of objects like the leaf, because none of us goes through life thinking “now I am seeing an external object; now I am hearing another external object; now I am feeling an internal feeling.” Everything in our experience overlaps with and is affected by everything else, and indeed what makes the experience of a leaf “utterly individual” is not only its spectacular shade of orange but what takes place ‘inside us’ if it happens to combine with the evening to spark an overwhelming sense of uncertainty or the fleeting memory of a walk with an ex-lover or what have you. Okay. And these phenomena might be susceptible to description — if I were to claim that they are completely unassimilable by language then literature might be rendered impossible, and I happen to like literature very much — but the descriptions of them must always rely on proximate, pre-figured concepts, any number of combinations of which might be equally plausible in attempting to make intelligible for the addressee the experience experienced originally by the speaker or writer.

Even as we know that both “leaf” and, say, “joy” or “melancholy” are sounds that have been arbitrarily assigned to arbitrarily-delineated patterns of phenomena in our experience, it is much easier to imagine that “leaf” will evoke a precise and relatively unambiguous meaning from one person to another than “joy” or “melancholy,” by the very simple fact that we can easily imagine two people experiencing exactly the same leaf and probably cannot imagine two people experiencing exactly the same melancholy. And I suppose this is why in my own efforts to write in the light of these charged and difficult-to-sort ‘internal’ elements of my life, including within this piece, I find myself listing so many concrete nouns and events: these take place on the side of the experience that is readily made linguistic, while the clouds of associational and emotional context, which in actual life are inseparable from the so-called external object, always shift and dance away from the grasp of the writing.

Ahem. Am I really still here attempting to capture something in the grasp of the writing?

In this pull I find the two contradicting desires that motivate what I am doing here, now:

the yearning for language to make it possible for me to become entirely intelligible (how lonely if it can’t!) and

the desire (springing from the impossibility of satisfying that yearning…) to do away with the whole set of pictures by which we imagine intelligibility in language might be possible.

Both of these desires being doomed, I am left with glacial harmonies from a stack of books, the mystery of gardens from the day and the page that makes it (dutch bros cup crushed in safeway parking lot, burning with the feeling of inside and outside), and I am left with the air conditioner humming, an empty postcard.